- The Institute

- Research

- Dictatorships in the 20th Century

- Democracies and their Historical Self-Perceptions

- Transformations in Most Recent History

- International and Transnational Relations

- Edited Source Collections

- Dissertation Projects

- Completed Projects

- Dokumentation Obersalzberg

- Center for Holocaust Studies

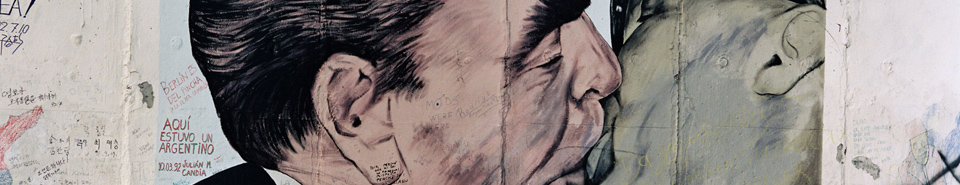

- Berlin Center for Cold War Studies

- Publications

- Vierteljahrshefte

- The Archives

- Library

- Center for Holocaust Studies

- News

- Dates

- Press

- Recent Publications

- News from the Institute

- Topics

- Munich 1972

- Confronting Decline

- Feminist, Pacifist, Provocateur

- Der Mauerbau als Audiowalk

- Digital Contemporary History

- Transportation in Germany

- Envisaged Futures at the End of the Cold War

- From the Reichsbank to the Bundesbank

- German Federal Chancellery

- History of Sustainabilities: Discourses and Practices since the 1970s

- Changing Work

- Democratic Culture and the Nazi Past

- The History of the Treuhandanstalt

- Foreign Policy Documentation (AAPD)

- Dokumentation Obersalzberg

- Hitler, Mein Kampf. A Critical Edition

- "Man hört, man spricht"

- Dictatorships in the 20th Century

- Democracies and their Historical Self-Perceptions

- Transformations in Most Recent History

- International and Transnational Relations

- Edited Source Collections

- Dissertation Projects

- Completed Projects

- Dokumentation Obersalzberg

- Center for Holocaust Studies

- Berlin Center for Cold War Studies

Dictatorships in the 20th Century

Following the First World War, the 20th century was marked by a fundamental opposition between democracy and dictatorship. While the war accelerated the development of parliamentary democracy in Europe, authoritarian forms of government, geared toward the mobilization of the masses and resources on a large scale, developed as well. At this time, Bolshevik rule in Russia emerged as the first dictatorship of a new, totalitarian kind. Between 1917 and 1989/90, a wide variety of dictatorial forms of government existed in Europe alongside democracy.

The rise of dictatorships at a time when democracy initially seemed to be asserting itself in Europe, as well as their internal formations and transformations, their relationships and interdependencies, their downfalls, their aftermaths, and their reassessments, and lastly their typological similarities and differences are all themes that remain themes central to research in contemporary history. The National Socialist (Nazi) dictatorship is studied nowhere more intensively than at the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History. The foundational work of the IfZ on the political and social history of the Nazi regime is being continued and expanded in the field of cultural history. The IfZ complements its work in the area with research on the two other major European dictatorships: Mussolini’s Italy and the Soviet Union under Stalin. The structures and practices of rule in these states are related to and compared with those of other dictatorships.

The research on Stalinism extends beyond 1945 to the second German dictatorship. In doing so, the IfZ does not isolate the history of the Soviet Occupation Zone and German Democratic Republic, but treats them as part of the Soviet area of hegemony and the “German-German” context, placing them within the overall course of 20th-century German history. This opens up points of contact with research on dictatorships before 1945. The IfZ is also making a substantial contribution toward the filling research gaps on central topics in GDR history per se.